If anyone has watched American Idol or even grew up watching the Gong Show, you know how amateur night works and how funny it can be. Back in 1906, there were several burlesque, vaudeville theaters in Milwaukee which offered their own amateur talent shows giving people the opportunity to perform in front of an audience and win prize money if they were good enough.

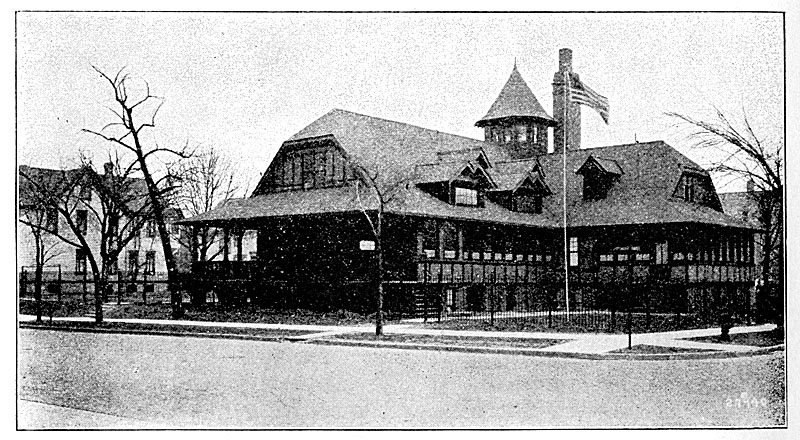

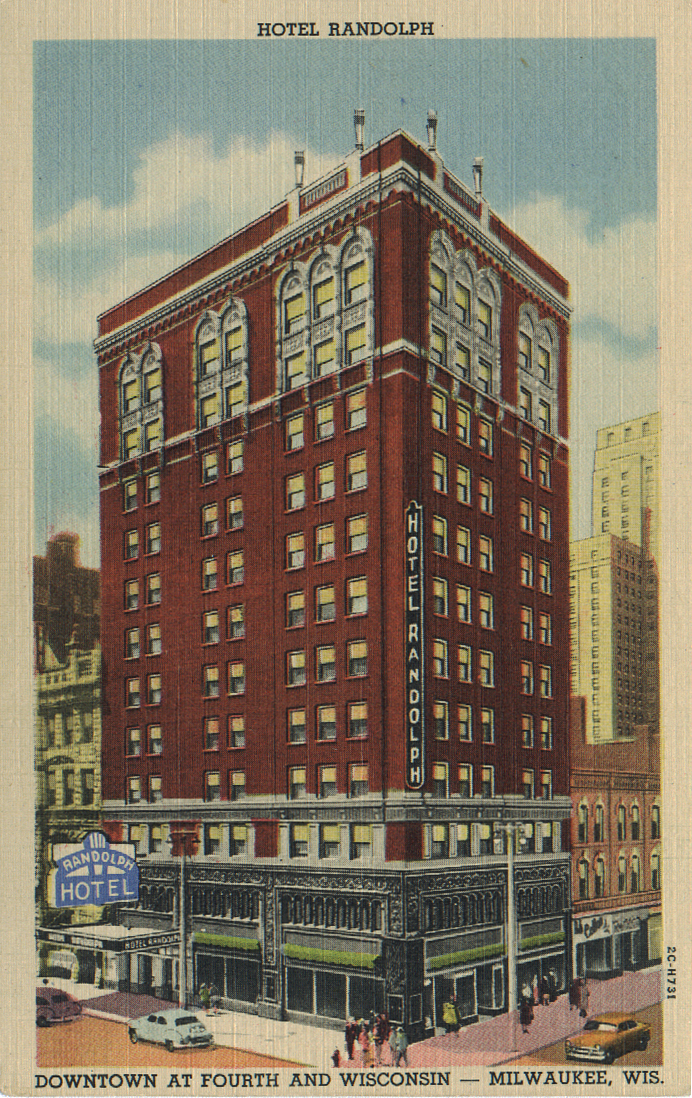

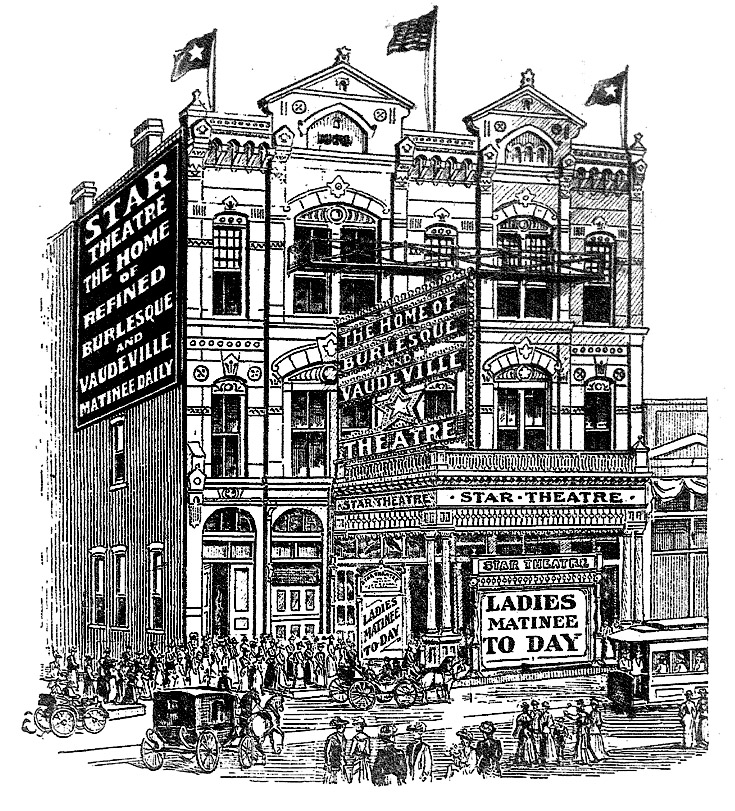

The following article from the Milwaukee Free Press covers one night in an anateur talent show at the Star Theater. The Star Theater was located at N. Plankinton Ave. on the east side and north of Michigan St. It was torn down in 1914 for the expansion of Gimbels. The picture below shows how it looked.

The article that I transcribed here tells about several performers who tried to win the first and second prizes offered and either won or lost horribly. It is fun to try and picture a packed theater watching these amateurs perform!

Milwaukee Free Press, March 25, 1906

Get the hook! A Night With Amateur Thespians at the Burlesque Theater

It takes a brave amateur to face the audience that assembles at the Star theater on Thursday night. But numerous Milwaukee folks, who think they possess talents, vocal, histrionic, acrobatic or terpsichorean, make their appearance there once a week and endure an ordeal calculated if they survive it to make real professionals of them in one trial.

Thursday night is “amateur” night at the Star, which means that after the close of the regular performance, the amateur aspirants for theater fame are allowed to do their turns, and take what’s coming to them, if they fall short. Most of them do, as a rule, and howls of derision from all over the theater but especially from the gallery, assail the awkward beginner.

“The hook, the hook! Get the hook! Get off!” shout the spectators.

These cries are the signal for the backdrop to be lifted, while a stage hand reaches forth a long pole, terminating in a sickle-like prehensile contrivance that grasps the performer and hustles him away back, while the drop descends and hides him from view.

The scheme works so effectively as to suggest it might be used as a test for some professional players who persist in inflicting themselves on a suffering public, and who might thus be discouraged and induced to go to work for a living.

But the chief purpose of “amateur” night is to furnish hilarious fun for the spectators. For the lamer the efforts of the amateurs, the more excuses to cry “Get the hook!” and enjoy the forcible removal of the tyre from the stage.

But to the closer observer of the player and his art, “amateur” night affords some interesting object lessons. The most conspicuous failing in the novice, even though perhaps possessed of natural aptitude and talent, is lack of confidence. And this is noticeable the instant the performer sets foot in view of the spectators. It is betrayed by the hesitating step, when walking toward the middle of the stage, and by the seeming fear to go as far as the center, as though the performer dared not get too far away from the wings. And then if it is a song the amateur is about a perpetrate, the first two or three bars are scarcely audible.

With the professional, the behavior is in striking contrast to this. There is not a vestige of timidity in his confident stride, ingratiating smile and loud voice. And confidence is half the battle.

Last Thursday night at the Star one of the amateurs was a colored boy, who was down for a song. But he was too timid to walk down the stage in front of the leader, and feared to let his voice out. It was a musical organ, but he had not sung two notes before the crowd in front Began to yell:

“Get the hook! Take him off!” And they did.

The boy’s gingerly walk and feeble beginning betrayed stage fright. That was nuts to the gallery but disastrous to the lad.

A child soprano, a girl of 10 or 11 years, quite pretty also made a bad start, whereat the people in the gallery hooted and clamored for “the hook” but it is not used on girls and she bravely sang two verses though she looked anything but happy. The demonstration made her lose the key in the first verse and the result was torture to the ear.

There were nine acts on the amateur programme, of which the fifth afforded the most hilarity. It was the acme of asinine amateurishness.

Two brothers, it was announced, would oblige with comic songs. They had no sooner appeared than pandemonium began. Their costumes were outlandish, but in the remotest degree funny, and their make-ups hideous, their faces reflecting garish daubs of red paint, in no sense comic, picturesque or human. They were perfect exemplifications of amateurism entirely untamed and uncontrolled. When the orchestra started to play, they did not begin to sing, but looked foolishly at one another, grinned in a silly way over the footlights, until at last the backdrop ascended and one of the freaks was hauled off. But the other remain for fully five minutes longer, not seeming to comprehend that the act was over. It was a pathetic exhibition.

Then came the gem of the programme.

“Mickey Daly will sing,” was the announcement.

And a black-eyed little girl with raven hair and olive complexion, resembling rather a daughter of southern skies, than of the Emerald isle, came out and sang “Cheyenne.” Her voice was full of sympathy and her eyes twinkled expressively as she sang. Deafening applause greeted her, and in response she sang “That Little German Band.” She made no gestures, but her countenance spoke volumes.

The next act was a wire walking performance, by Master Nevaro, Jr., whose brothers are professional equilibrists. The boy performed difficult feats with professional-like confidence. He was awarded the second prize, $2, the first prize, $5, being given to the little Daly girl, by vote of the audience.

G. Reno, a youth of 21 or thereabouts, made his appearance as a buck and wing dancer and the spectators started in to howl him off, but cries of “Get the hook,” didn’t fluster his feet a bit, and they were all he was using. He just smiled and kept on dancing, until finally dexterous steps changed the hooting into applause.

Mr. Schlieve, the “iron jawed man, chair balancer and rod breaker,” appeared on the scene followed by a suckling pig, which he lured about the stage, with a bottle of milk equipped with an attachment which piggie easily to his mouth. The spectators laughed heartily at the pig, who betrayed no amateurish anxiety over his act, and while they laughed, Mr. Schlieve took off his coat and vest, and began to balance aloft, from one to five chairs, their weight all resting on his jaw. So he escaped the peering his absurd facial make-up would have unquestionably provoked had he appeared without his little pig.

The amateur diversion closed with a peppery two-round go between two bantam-weight brothers, that proved thoroughly enjoyable.

The amateurs appear at the stage door of the Star, on Thursday night, before the regular show begins and stage manager Hoolihan takes their names and arranges the order of their turns, which as a rule do not exceed ten in number. they provide their own costumes, though as a rule they appear in their ordinary street attire, and are allowed to make up their faces, should they use grease paint, which they seldom do, unless perchance an amateur imagines he is cut out for a funny man.