During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Milwaukee River above the dam near North Avenue was a very popular swimming and recreational spot. There were plenty of swimming schools and pleasure boating was also a fun activity. This article tells the story about the first swimming school on the river which was founded by Julius Rohn. An article I published in 2011 has an aerial photograph showing where Rohn’s was located.

Milwaukee Sentinel, June 21, 1908

Milwaukee Has Oldest Swimming School in the Country, Over Half Century Old

By Charles Tenney JacksonMilwaukee’s “ol’ swimmin’ hole” is to have a recrudescence of usefulness. Rohn’s place up Milwaukee river, known familiarly, even lovingly to every native son of the good old town, for here every mother’s son of them learned to paddle “dog fashion” and dive like a muskrat long before the days of the hifalutin overhand stroke, before fancy trunks emblazoned with monogram and club colors were ever heard of, is to be restored and a sturdy aquatic athlete of local renown is to reopen the school on a scale that dwarfs its former memories.

“The ol’ swimmin’ hole of Milwaukee” is the oldest swimming school in the United States. Away back in 1856 Julius W. Rohn came over from Leitmoritz, Bohemia, and picked out that little plot of ground on Milwaukee river, 50×150, which has a loved fame to all Milwaukeeans greater than any spot in all the city.

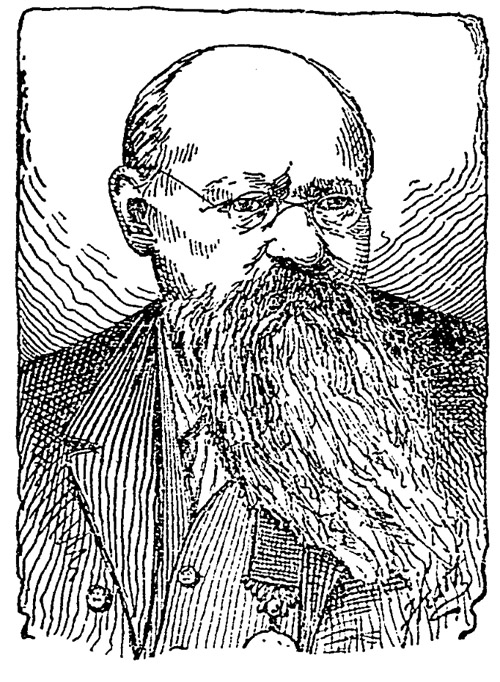

Julius Rohn knew how to swim ere he saw the land of the free. He had been a swimming instructor in the armies of Austria and an ardent lover of athletics since his childhood. When, in 1855, he came to Milwaukee from New York, “the ol’ swimmin’ hole” up the river was a picturesque bit of wildwood – nothing more. Mr. Rohn purchased the piece. Milwaukee was a thriving immature city some miles down the river then and it seemed a far call to the day when folks would come out as far as the old dam to take swimming lessons or disport in the pools, but the young Austrian soldier set up his swimming school and let it be known to the city. Its patronage at first was not flattering to success. In those days there were no street cars and people on warm summer afternoons and evenings had to drive or walk up the old canal road now Commerce street to reach Rohn’s school. But even the old time kids had found out the loveliness of Milwaukee river, its placid pools and rippling rapids; many a skinny shanked youth had learned in the upper river, regardless of instructor or the blushing askance of the chance passerby, the perplexing details of the breast stroke and the uncanny sensation of trying to float chin high out of water for the first time.

To the young city of Milwaukee in the fifties, nestling below the sylvan river reaches, came the Austrian soldier swimmer. He was six feet tall and of powerful build, quick of eye and judgement, as many generations of Milwaukeeans were to learn. It was these qualities that made “Rohn’s school” famous, and which now gives his sons just pride to say that in fifty-two years of its existence but one life was ever lost of all the thousands of the instructor’s pupils.

In this little plot of land above the old wooden dam of that day, Julius Rohn established the first swimming school of America. He had a tiny shanty along the water margin, and here with his young wife he lived in the summer and here his four sons grew to be as expert in the water as their father. Mr Rohn had married Ida Seidemann of German birth and devoted his time thenceforward to making Rohn’s school the place of all lovers of the water. As the city down the river grew more and more, people found their way of Sundays and holidays to the swimming school. Merchants and brewers and professional men came to perfect themselves in the pool below Rohn’s bathhouses and to leave their children in his care, for his watchfulness and care became a proverb and sometimes a strict disciplinarian he was. The instructor made a strict rule that none of his young charges should try to swim across the river, more than one adventurous lad dared to disobey this, for when one was half way over, it appeared safe for the culprit to ignore Teacher Rohn’s warnings and paddle to the east shore.

But woe to the culprit when he came back. There are middle aged men in Milwaukee’s business life today who can remember how the former Austrian soldier seized the shivering youth, laid him all bare and wiggly across his knee and soundly smacked him where it would reach the most superficial area that would feel a smack from a large firm hand.

Wow! And without any trousers on and wet and squirmy. No wonder some of these Milwaukee men remember Julius Rohn!

But he taught them how to swim. The modus operandi was much as that of today, though many new racing strokes have been added. The Milwaukee river at this point was and is about 430 feet wide with an average depth of eighteen feet. In those days, after its first year below the dam, near where Becker’s tannery now is, the school clung to the bank just across from the heavy woods later known as Sigel’s camp during the civil war. The space before it was a clear, fine pool, as clean as the lake water and along the platform over the water Instructor Rohn conveyed the kicking youth with a hand under his breast while carefully telling him the stroke and the way to breathe.

There was a rule in those days that no lad could leave the protecting tether under Rohn’s guidance until he was able to swim thirty minutes unassisted. Of late years this wise, if arbitrary old rule, was lessened to ten, and today there are no words that will call up more pleasant memory to the generations of the native born than these: “Say, are youse swimmin’ free yet?”

“No, but I’m going to swim free next week.”

That meant the aspirant had graduated. And what a glorious independence it was! No more instructor at the end of the rope; the youngster could dive off the boards and breast it out to midstream as much as he pleased and even risk a spanking to gain the further coveted shore.

“I believe it is safe to say that every boy in Milwaukee, now grown beyond his twenties, has swum at father’s place,” said Julius Rohn Jr., the other day, “and we have had pupils from every state in the union during the long time the family conducted it. It was not uncommon for father to teach 200 boys there during the season and in the fifty-two years that would make more than 8,000. And as to the number who have swum there, apart from the students, it is simply incalculable in the half century. Our bathhouses and swimming privileges used to open at 5 o’clock in the morning and close at dark, and on hot days there would be boys there at the opening. Some days at least 600 boys have been in the water, and as the season lasted from the first of June to the middle of September, you can estimate roughly how many lads used to seek the river here. I think every lad of the old German families has been taught by my father. The charge used to be $10 for the complete instruction, and all sizes of youngsters were taken. I think Robert Nunnemacher was the youngest father ever taught, for he showed him how to swim at the age of 6 years. The record that our school had for its freedom from accidents was remarkable. Excepting the drowning of one young woman, there never was a fatality at Rohn’s in the fifty-two years. My father was granted a gold medal from the government for saving life; but the particular instance for which this was given was but one of many. He rescued at least seventy-five drowning persons during his career. He was a big, strong, fearless man, and had the confidence of every pupil in the school as well as that of all the Milwaukee river frequenters.

“In the early days when I and my three brothers were young, father used to have much trouble with toughs who came up from town Sunday and created disturbances. We had a lunch counter and bar with our bathhouses and these fellows from the city – for Rohn’s was then outside the limits of Milwaukee – a great many times started a row. They got worsted once or twice and then after that they used to come up on purpose to “do up that old Dutchman.” Then all of us boys came to father’s help and the five of us cleaned out those gangs so thoroughly that the trouble soon stopped. The police could offer no assistance, of course, as we were not in the city. The family practically lived there in the shanty on the river during the summer when father’s school was open. I think that all the best known citizens of Milwaukee for generations learned to swim. The bathhouses were a big feature of the business up the river in the days before the city water works were effective over large areas; but when people got so they could take a bath handily in their homes they no longer came to the river in such numbers and we gave up the houses.

“But the swimming school continued in popularity up to the time of father’s death thirteen years ago. For many years our brother Louis continued as swimming instructor while my mother managed the place. But after their deaths, the others of us were too engrossed in other business to carry on the old school and it rather ran down.”

But better days are coming again for “the ol’ swimmin’ hole.” Although the Rohn brothers have sold the school, site and buildings to the Wisconsin Lakes Ice and Cartage company, have now been leased by Edward Dierolf, who for five years was an instructor at Rohn’s and is a capable teacher as well as an expert fancy swimmer and diver. Mr. Dierolf was for many years in charge of the famous Lurline baths in San Francisco and also instructor in the best known schools in the west and has friends among all the thousands who have patronized Rohn’s in the last half decade. The ice company will expend $3,000 in fitting up the old buildings and Mr. Dierolf will this summer conduct “the ol’ swimmin’ hole” for the benefit of Milwaukee lads and girls who wish to learn the art, while making it in every way the same old spot of fun and laughter that it was for more than half a century.