The East Side Commercial Historic District: From Controversy to Catalyst

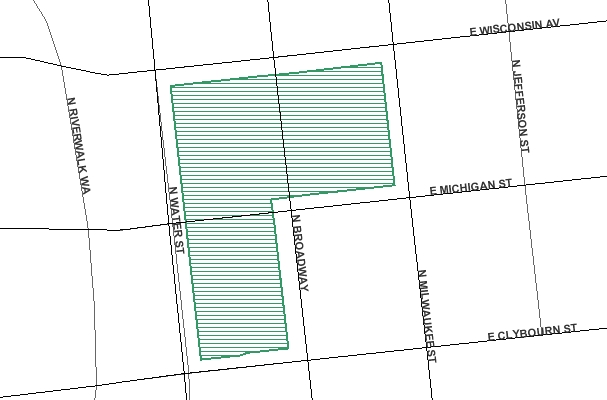

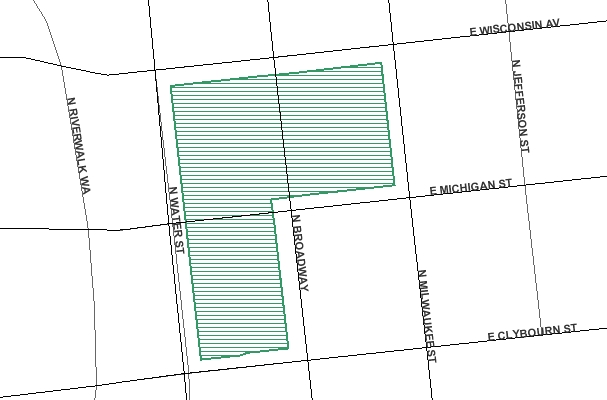

The HMI panel discussion on Thursday night, January 17th talked about many recent issues and changes that have happened in the East Side Commercial Historic District. This locally designated historic district, under the jurisdiction of the City of Milwaukee Historic Preservation Commission (HPC) is shown here:

The controversy which spawned this discussion began in 2010 with plans by Wave Development to build a new 200 room Marriott Hotel in place of five historic buildings within the district. The developers fought the HPC rejection of their initial plans. Those plans ran counter to preservation guidelines put in place for the district in 1987 as well as the Preservation Ordinance. The ensuing battle between the developer’s public relations firm, the City HPC, and preservationists became a media event for weeks. When the dust settled, the developer revised their plans to save the Noonan Block on Wisconsin Avenue. The Preservation Ordinance was subsequently put in the spotlight with promises to be gutted by Alderman Witkowski because it was viewed as anti-development. It was amended in December of 2012 by the Common Council but with changes that made it stronger and not weaker. The final consensus was that preservation “makes good economic sense”.

UWM Professor, Matt Jarosz presented the history of the district and its importance as the virtual heart of Milwaukee since the first settlement. It is unique among similar American cities in not continuously redeveloping the land as time progressed. Many of the buildings within the district are 19th century interspersed with a few early 20th century buildings examples. Professor Jarosz went on to give a multitude of examples from his students on how this district could be improved to take advantage of the current impediments. Some of the best concepts took advantage of underutilized surface parking to build modern buildings that connect to historic buildings and offer updated access to those buildings. These new buildings would add larger entrances, elevator service, and other improvements to modern standards and codes without requiring expensive retrofits to the older, historic buildings. One example showed how a new structure to the south of the Iron Block could add features to it and the Zimmermann Block next door. Infilling adjacent to the Button Block would encourage re-use of the upper floors. Another interesting proposal was converting the public alleys into shared space that could be used as a semi-covered pedestrian space or for extended outdoor seating. His common theme was that intelligent, planned new development could reinvigorate the district and encourage property owners to invest in building rehabilitation.

Some of the other presentations of the evening included an overview of the work done by architect Mark Demsky of Dental Associates with the restoration of the Iron Block Building. Dental Associates took unprecedented steps in restoring features that had been removed from the building over 100 years ago including decorative cast iron urns above the Water Street entrance and intricate grape leaves on the columns. He researched the history of renovations and found a trove of information that would be overlooked by architects doing a basic renovation. When the building is unveiled in March it should be a showpiece of preservation in Milwaukee.

Steve Schwartz, CEO of the First Hospitality Group talked about his company’s work renovating the Loyalty building on Broadway and Michigan. They faced many challenges in converting the Solomon Spencer Beman designed masterpiece from an office building into a hotel with modern conveniences. As with many 125 year-old buildings, it had been remodeled many times over the years, removing or hiding some of the notable features. The First Hospitality Group has been involved in several adaptive re-uses nationally, this building being the sixth. The first was in Indianapolis, converting a former 16-story bank building into a Hilton Garden Inn in 2003. Adaptive re-use preserves details of historic buildings that couldn’t be done economically in a new building and creates an “experiential” space encouraging participation and use.

The final talk was given by Josh Jeffers, owner of the Mitchell Building with the work he has been doing the past few years in stabilizing the foundations of his building as well as the facade and roof renovations. The persistent problem of a dropping watertable downtown have resulted in the exposure of old wooden piles under building foundations to wood rot. In the Mitchell Building, it was found that many of the footings were unsupported because of the advanced state of decay of these pilings. The exterior of the building shows some effects of the settlement over the years. The work to repair the problem has been time consuming because nearly all of the excavation has to be done by hand in tight spaces in the basement. Great care must be taken to avoid further damage to the building. The area under the stone pile caps must be removed manually, the rotted piles must be cut out and a new concrete pile cap was poured in the excavated area. In addition, a new technology of using the building’s wastewater in a sub-basement drain system was used to keep the deeper wooden piles wet and free from future rot. This major investment in the building will keep it standing firm for many years to come.