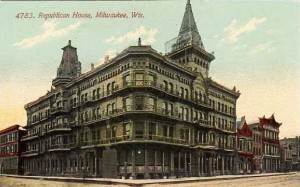

On the night of Saturday, March 29, 1930, there was a large fire at Milwaukee’s downtown Republican House. No one was reported killed, but many were overcome by smoke and carried from the building. The fire chief reported a cigarette in the laundry shoot was to blame for the blaze.

The Republican House stood on the northwest corner of Third and Kilbourn, now a parking lot for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. It was taken down in 1961.

The next morning’s Milwaukee Sentinel ran this interesting article on the history of the hotel. Some of the details differ slightly from other accounts I have read, but still it is of interest, I think.

The Republican House is rich in historic lore.

When built in 1836 by Deacon Samuel Brown for Andrew Clybourn, it was thought altogether too large for the business of the day. William P. Merrill, one o the pioneers of Milwaukee, had the contract for putting on the cornices, which still adorn the building and form a distinguishing feature. They were quite a curiosity in those days.

Linked with the building are many pioneers. Benjamin Church and Morgan L. Burdick are others who had a hand in its building.

The hotel was the scene of a big celebration when the ground for the ill-fated Milwaukee and Rock River Canal was broken by Kilbourn and others. It was there that William A. Webber put up the first billiard table in Milwaukee.

In those days the hotel was situated on Cherry street, between Second and Third streets. When the west side became more populous it was moved to the corner of Cedar and Third streets.

The original name of the hotel was the Washington House, which name was retained until about the time of the birth of the Republican party, when it was given its present name, its proprietor being an ardent republican.

For many years it was conducted by Alvin Kletzsch and his brothers. Later its control passed to Ray Smith, Inc.

The hotel has had many distinctions. It was the first hotel in Wisconsin to install electricity. It also led in adopting the cafeteria style of serving meals on a large scale. It was the second hotel in the United States to have its own cold storage and refrigerating plant. It was the first hotel to build a convention hall in its own building.

It was Dec. 31, 1875, when the Kletzsch family took charge of the famous hotel. Charles F. Kletzsch, father of the boys, leased it at that time and conducted it without any notable change until 1880, when he purchased the property and erected the first unit of a number of additions. At that time Milwaukee had a population of about 69,000.

The old Republican house at that time was away from the center of business, but Kletzsch foresaw the development of Third street in the vicinity of his property, and in 1883 a second unit was added. A year later the corner building was razed and the two wings were connected by the Cedar street addition, forming one complete unit.

In 1888 the Charles F. Kletzsch company was incorporated, the elder Mr. Kletzsch retiring and turning over the business to Alvin P. Kletzsch and Herman O. Kletzsch , his sons. In 1892 they added the fireproof addition and in 1900 another unit was added, and this was known as the Third street addition.

A year ago the hotel again passed back into the hands of Alvin and Herman Kletzsch. Charles Karrow was installed as manager.

William George Bruce, close friend of the Kletzsch family owners of the Republican hotel, had retired for the night when called to be informed of the fire in the hotel.

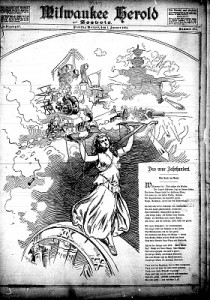

“It was one of the most famous hotels of the state,” he said. “It was for many years one of the most popular hotels in the city, especially with people from the central and northern sections of the state. It was the scene of many of the old social gatherings, those of the German-American element predominating.”

“The old hotel was started by Charles F. Kletzsch, who took it over when it was little more than an old boarding house. That was when it was a frame structure. Under his management it rapidly became noted for this wonderful hospitality and excellent table. It was soon torn down to make room for the first unit, built of brick and stone. The new Republican house continued to prosper and three times the building was enlarged by the addition of other units.

“When Mr. Kletsch [sic] passed away, two of his sons took over the management. Under the direction of Alvin and Herman O. Kletzsch, who continued the policies and methods of their father, the hotel continued to prosper. The boys added the Park hotel in Madison to their holdings and it, too, had a wonderful success.

“Being not far from the old Exposition building, where all of the state political conventions and caucuses were held, the hotel, under the skillful direction of Alvin and Herman, was considered exactly what its name said, the republican hotel of the state. In its guest rooms and meeting rooms many a candidacy has been doomed to bud and die unseen and unknown. Many a prominent figure in state politics had his first acceptance in those secret meetings of the old republicans in the old Republican hotel.

“Some years ago the Kletzsch brothers sold their hotel, but not the real estate, to Ray Smith of the New Pfister hotel. He, too, made a success of the place and later disposed of it to Harry Newmann, one of the owners of the Kirby house when that was torn down. Some two months ago, Mr. Newmann wanted to retire from the Milwaukee hotel business and the Kletzsch boys again came into possession of it.

“Herman O. Kletsch [sic] is still interested in the German-American activities and is one of the leaders of the Steuben society of Milwaukee. Another brother, Dr. Gustav Kletsch, is proprietor of the Nutricis [?] farms, and Arthur Kletzsch is vice president of the Morris Fox company, investment securities dealers.”

Dennis Pajot

Milwaukee