Back again to see who can guess where the mystery building in the accompanying photo was located. This building is still there although I doubt anyone can recognize it. Hint – it is no longer a car dealership. Where was the mystery building?

This is a crop from a larger picture that I have. The exact same picture can be see in the MPL Milwaukee Waterways digital collection here. It shows an area that has changed tremendously starting in the early 1990s and continuing today.

Originally the area was a recreational spot with boating and swimming and ice skating in the winter above the dam. This picture from 1948 shows many coal yards piled up in the train switching yards and also west of the Humboldt bridge. Rohn’s swimming school still stood although it didn’t last too much longer. By then, the runoff from the coal piles and other industrial pollution was making the area unfit to swim.

Sometimes newspaper articles from the 19th century were written as if by a poet in prose that tried to capture the spirit of a place. This particular article from the Milwaukee Sentinel distilled a streetcar ride from Bay View up to Whitefish Bay in a short article but rich in its description. It gives a rare glimpse at the sights of a long gone Milwaukee.

CONTRASTS OF A CAR RIDE

A through passenger on the Russell and Oakland avenue line from Bay View to Whitefish Bay may amuse himself with the contrasts presented during a ride of an hour and a half. I don’t think of any one-line journey in the city that equals it for versatility. A person interested in chemistry can find food for thought in the suggested contrast between permanent traces of sulphuretted hydrogen at Kinnickinnic bridge and the basswood blossom perfume at the Lindwurm road crossing. The antiquarian may reflect on the contrast between the silent smokestacks of old Minerva furnace and the closed forge of the Luecke blacksmith shop north of Humboldt crossroad. There are also many contrasts of taste, contrasts of architecture, of arboriculture, botanical contrasts as well as ethnological contrasts, yet on fine weather such as generally prevailed since St. Swithin’s day, a kind of universal beauty has spread along the way, modifying the high lights and enlivening the shadows of a picture a dozen miles long.

The starting point is Delaware and Pennsylvania avenues, three blocks from Lake Michigan, yet so near that the sound of the waves on the beach is often heard, and the cliff swallows flitting from their nests in the bluff often perch by hundreds on the telephone wires. A feature of the undergrowth here that cannot be ignored is the thrifty character of the melilotus plants, south and east. They have in some cases covered roads and sidewalks with a forest four feet high. It is essentially an inland view that greets the eye as the car moves north, with glimpses of strips of forest trees to right and left. On Russell avenue a bit of swamp scenery appears, with typhad spikes growing tawny in the sun and water eternally distilling the color from roots. Churches of four denominations have a place before the corner of South Bay street is reached, and between them appear a few large houses of the old style, with grounds originally extensive, but curtailed to meet the demand for city lots. A community of modest residences and stores spreads away on every side, bounded on the north by coal yards and manufacturing places.

As the car turns into Clinton street, one of the pioneer houses of the city, the old Horace Chase residence, is worthy of note, and before it is a public fountain, the only one on the line except the Bergh fountain on market square. For three miles the car runs along what was once the principal retail business street on the south side, from Horace Chase’s subdivision through “Milwaukee proper” to “Walker’s Point.” It is a manufacturing district now, with smoky atmosphere and cinders everywhere. The restaurants of the dock laborers around Walker’s point can be viewed hastily, as well as the brick pavement in front of the old Axtell house and the brick block that Col. George H. Walker built fifty years ago.

Glimpses of the deep-blue waters of the lake are afforded as the side streets flit by, and at the Walker’s point bridge its dazzling expanse spreads to view through the straight-cut, beyond the docks. Odors of river slime, tempered by sunrays, bubble up, and the car may be detained while some long steamer goes through the draw.

A half-mile of wholesale business establishments and a mile of retail stores, well peppered with saloons, is followed by the tannery district, in which the aroma of hides strive for mastery with that of tan bark. If there is any choice, the latter seems the least disagreeable. Remains of the old squatter dominion, formerly unquestioned at the head of Jefferson and Jackson street, claims a glance from the architectural student, who expects to build inconvenient houses.

A picturesque river view is seen at Boyleton place, and at North street bridge and then the car passes monotonously along North avenue and through Murray’s addition and Mitchell heights to Oakland avenue (formerly High street). The air from here to the end of the trip is clear and delightful. Beyond the Humboldt cross-road, farm land sprinkled with small houses is on one side and thick groves of birch and oak on the other, with one or two pretentious country places between. This sort of landscape continues to Whitefish bay, giving surprises constantly. One superb bit of water color, showing the coastline to Fox point and the whole bay, is brought to view.

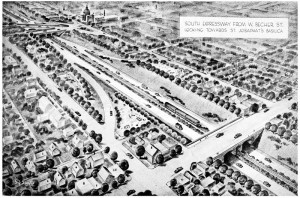

Back in 1949 a study was completed that analyzed the best routes for expressways in the city. Many of the plans went ahead to be completed 15 and 20 years later while some were changed immensely. During the time period from these early plans to the time of final construction many things changed in the city. The post war building boom opened up many new tracts of the city which led to a radical shift in population. The late 1950s brought the death of the North Shore railroad line.

The following sketch shows a plan that incorporated the old North Shore railroad into the new expressway. This design gave the railroad its own right of way that got rid of the bottleneck on South 6th Street where the railroad ran previously. Unfortunately with the North Shore’s demise these plans were dropped.

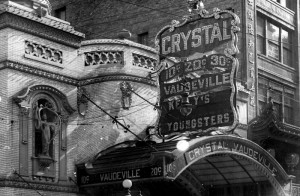

The west side of downtown was the entertainment district in the early part of the 20th century. West Water Street, 2nd street, 3rd Street, and Grand Avenue had numerous variety, vaudeville, and early movie theaters. The Crystal Theater was a small vaudeville house at what is now 726 N. 2nd st. It played musical, comedy and dance acts. Slapstick acrobatics and trick riding were common as well as bawdy musicals. New shows were regularly scheduled with a variety of performers traveling from city to city.

The theater finally started showing films in August of 1925 with “The Folly of Youth” but lasted only a few years more until it closed, unable to match the larger and more popular movie theaters.