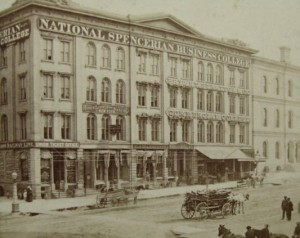

Any guesses where this early Milwaukee view of the National Spencerian Business College was? This was somewhere downtown and we are looking sort of northeast. The building was replaced in the 1920s. Sorry eddie, no cars although the wagon looks like it could be a 1879 Dorsch.

Author and historian, Ellen L Puerzer has a new book out. I’ll let her explain:

To anyone interested in octagon houses (50 were built in Wisconsin of which 27 remain)

My book has been published. It contains photos and histories of the 900-some octagon houses that were built in the US and Canada.

Information about ordering the book can be found here. Some sample pages are shown on the website and it looks like a great volume listing all of the surviving octagon houses and many that are demolished.

There have been quite a few recent updates to the OldMilwaukee.net Downtown Building Database. This is a great resource for anyone interested in learning about downtown’s architectural history and includes buildings long demolished. I try to continuously update the database with newly found information and links to building information on other websites.

Some of the updates are links to images from the Wisconsin Historical Society’s newly updated Architecture and History Inventory (AHI). Make it a point to stop by their website to learn about other buildings in Milwaukee and the rest of the state.

Here is a new article written by Dennis Pajot about one of the early pitchers in the Cream City Baseball club.

“A year or two ago I started a minor project to find what happened to the players on Milwaukee’s first major baseball team, the Cream City Club. Of the 9 regulars on this late 1860s club I could find information on most, but not enough to put together whatever I was trying to do. Then a few months ago Gary Rebholz and I were talking at the library and he told me he had found a death notice on an old ball player named Archie McFadyen. He asked if I was interested and I told him I certainly was. Gary was kind enough to send me (and translate from the German) the death notices he found. With this information I could find look for further information in the Milwaukee Journal and Milwaukee Sentinel and together with the information I had, put together something on the life of Mr. McFadyen.”

According to the Milwaukee Sentinel of February 11, 1900, “one of the most even-tempered and courteous men in the city” was the doorman to Milwaukee’s Chamber of Chambers, Archie McFadyen.

Archibald McFadyen was born in Erie, Pennsylvania in 1839. Archie’s father, Archibald Sr., brought his family to Milwaukee in June of 1842 on the high pressure steamer, James Madison, captained by Archie’s uncle John McFadyen. The senior Archie McFadyen was a sign painter by profession. It was said the signs he painted were done so well they lasted as long the buildings on which they stood. The McFadyen family took up residence on Van Buren Street.

While little is known of our Archie’s early years we do know he was in active service with the volunteer Liberty Hose Company No. 2 of the Milwaukee Fire Department. We also know in the late 1860s McFadyen was in the Merchants’ Zouaves and at some point became a member of the Knights of Pythias.

After the Civil War young men in Milwaukee became interested in the game of Base Ball that was becoming increasingly popular around the country. Archie was one of the young men enthused with this game. The Cream City Base Ball Club was formed in late 1865 and a match game between members was played at Camp Scott (on Prospect Avenue near today’s Royal Place) in early November. McFadyen was the pitcher in this first match game, giving up 30 runs. Fortunately his team scored 36 in the seven inning affair.

The Cream City Club took on a more formal aspect in 1866 and played a number of out of city clubs. One of these games was a Decoration Day game against the Capitol City Club of Madison at Camp Randall. The Cream City Club left for Madison in high spirits, perhaps fueled by the news that the young ladies of Madison were “preparing to crown the victors after the manner of the ancient Grecians.” Cream City won the game 48 to 15, McFadyen’s pitching “completely demoralizing” the Capitol City nine.

Play continued for the Cream Citys through the 1866 season, including tournaments in Illinois. The local club went on to win the Wisconsin State Championship. In the 1867 McFadyen was elected secretary of the club. Archie continued pitching until later in the season when the Cream Citys found a new pitcher. McFadyen changed to shortstop. For the second straight year Cream City held the state championship.

1868 found Archie at shortstop again. But baseball was changing. Members of the Cream City Club, as all baseball players in Milwaukee, were amateurs. But professionals were filling the ranks in other major cities, and some of these professional teams played the Cream Citys.

Archie continued to play shortstop for the Cream City Club, in addition to being the team captain in 1869. When the club’s regular catcher could not play, McFadyen took over behind the plate. He was in this position when the Cream Citys played the famous 1869 all-professional Cincinnati Red Stockings. Archie managed one hit and to score a run in the home team’s 85 to 7 loss to the famous Red Stockings. McFadyen continued to play with the club until 1870 when professionals took the front seat in baseball across the country.

In December 31, 1867, Archibald McFadyen had taken over the job he would be best remembered for: doorkeeper of the Milwaukee Chamber of Commerce. Archie’s job description at first was more than doorkeeper. It was also his duty to sweep out the chamber and performed duties later delegated to others. He was a bit of a utility man. McFadyen was at first doorman at the old Chamber of Commerce building at Michigan and Broadway. This building was torn down in 1879 and Archie stood guard at the temporary quarters occupied by the chamber in Munkwitz’s building up the street on Broadway. The new Chamber of Commerce building was opened in the fall of 1886 and still stands.

While at the door of the Chamber of Commerce McFadyen made the acquaintance of many financiers and speculators—both those extremely successful and those who lost all their money. It was said his “unfailing good nature and willingness to accommodate made him a favorite with every one.” He was just as skillful at introducing new members of the bulls and bears as he was at keeping non-members out.

Of the many he met, Archie had a few stories on some of the most famous. He though the most interesting character on the floor was Daniel Newhall. Not only was Newhall a smart speculator, but a fair and honest man, who was helpful to charities and passed money around freely. Other speculators and investors who stuck out in Archie’s memory were Edward Sanderson, Peter McGeoch, Alexander Mitchell and Phillip Armour. Archie had a funny story about Armour once giving him a cigar to smoke after dinner. McFadyen, who had never seen Armour smoke on the floor, marveled at Mr. Armour’s constitution, judging from the cigar. When Archie smoked the cigar, he said “It almost took my head off.”

Archie McFadyen had the desire to round off his service at the Chamber of Commerce at 50 years. But after more than 48 years his family persuaded him to retire his post after a serious operation. It was thought it was doubtful if any other man held the position at the door of a commercial organization in the United States as long as Arche McFayden had held his position as doorman in Milwaukee.

Archibald McFadyen passed away on October 8, 1921 at his home at 650 Van Buren (later address changed to 1232 North Van Buren). He was survived by his widow, Jennie Louise, and two sons and two daughters. One of his sons was Alexander McFadyen, a nationally known pianist and composer. Archie McFadyen was buried at Forest Home cemetery.

Dennis Pajot

Milwaukee

The large number of German newspapers that were printed in Milwaukee at one time are largely forgotten. Most readers would be hard-pressed to name even one. A few survived into the 20th century but were slowly smothered by competition from the stronger English-language dailies and forced Americanization of their readership.

In 1889 the Bennett Law forced all public and private schools to teach the major subjects in English. Although the law was repealed a few years later, it led to the younger second generation of German-Americans to be more dependent on English rather than their native language. By 1899, many of the country’s leading German language newspapers were starting to cease operations. World War one and Two together helped to squash the pride many felt in their German heritage. The Milwaukee Herold continued to be published in Milwaukee until 1932.

This 1898 article tells the history of the beginnings of the larger and most influential German newspapers in Milwaukee during the mid 19th century.

Milwaukee Sentinel May 8, 1898

MILWAUKEE GERMAN JOURNALISM.Some Reminiscences Suggested by the Disappearance of The Daily Seebote—Some of the Editors Who Rose, Flourished and Died—First German Paper Appeared in September, 1844.

The absorption of The Seebote by The Herold last week and the suspension of the former as a visitor to the homes of the Germans of Milwaukee, was a consummation lamented by a large number of old settlers who, even if unable to read the text of The Seebote, regarded it as one of the institutions of the city lively to endure for all time. While not in itself the oldest German newspaper in the state of Wisconsin, The Seebote had absorbed all its predecessors in the city, and by this means stood at the top of the list as the senior German paper of the state when it went out of existence with it’s last issue a week ago this morning.

German journalism in Milwaukee antedates the city charter. The first paper published in that language was The Wisconsin Banner, which made its appearance in September, 1844, with Moritz Schoeffler as editor, It was a weekly publication, and was printed on a Rammage press, which, contrasted with the web perfecting machinery at present used in the production of the newspaper, shows a remarkable advance in the art of printing.

The Rammage press would only admit of the printing of one side of a single page at a time, and to print the four pages of that day required the paper to be run through the press four times. On the authority of the Hon. P. V. Deuster, who was employed as apprentice, or rather “printer’s devil” in the old Banner office, the Rammage press was brought to Milwaukee from Green Bay, where it gained the distinction of being the first printing press ever brought to Wisconsin, or rather the territory that afterward bore the name, for the advent of the old printing machine ante-dated the naming Of even the territory.

The Wisconsin Banner was Democratic in its political predelictions, and as the Germans were flocking to Wisconsin in large numbers The Sentinel, then the advocate of the Whigs, realizing the necessity of counteracting the influence of The Banner among the new arrivals, started a German paper, which passed current among the people as the property of Fred Fratny. The venture was a losing one, and the publication was rechristened The Volksfreund, made independently Democratic in its politics, and devoted its energies to assailing The Banner. The latter paper however, continued to prosper, and Mr. Schoeffler built a printing office just north, of the present St, Charles hotel, on Market square on a leased lot. The building was finally removed further up the street, and is now doing duty as a residence at 522 Market street.

Moritz Schoeffler died Dec. 6, 1875. He was about 60 years of age at the time, He was one of the founders of the German-American academy, and was collector of customs under the administration of James Buchanan.

In 1855 Mr. Fratny died, and The Volksfreund was purchased by and became consolidated with The Banner as The Banner and Volksfreund, with Schoeffler & Wendt as owners and August Kruer as the editor, and was issued as a daily.

Mr. Fratny was bitter in his opposition to the Catholic churcb, although his wife was a devoted follower of that faith. He made a vigorous attack upon the Rev. Father Heiss, afterward archbishop, for refusing to bury an ex-priest in a Catholic cemetery. When he was taken down with his fatal illness, he called upon the members of a certain secret society of which he was a member, to remain with him during his last hours for fear that he might in his weakness yield to the importunities of his wife and allow a priest to approach his bedside.

In 1850 The Stimme der Wahrheit (Voice of Truth) was started in opposition by the Democrats. The editor of this publication was a character. Roessler von Oels had been a member of the German parliament at Frankfurt-on-the-Main in 1848, where he was known as “Reichs-kanarienvogel” (canary bird), owing to the peculiar cut and color of the clothing he wore. He had, previous to coming to this country, been imprisoned at Hohenasperg for political offenses, but had managed to escape. He was an eccentric man.

In 1852, July 4 coming on Sunday, the Germans wished to celebrate that day, but the Americans and church people objected and Roessler sided with the latter. After the suspension of his paper, which was short lived, he contributed to the columns of The Sentinel, and finally went to Quincy, Ill., where he established The Tribune, and died while engaged, in its publication.

The printing outfit which he owned in Milwaukee was purchased in 1851 by a stock company made up of Catholics, and The Seebote was started, the editor being Amand de Saint Vincent, who was accounted the best musician in the West at that time, and whose criticisms of the work of the Milwaukee Musical society, which was started in 1850, were considered of great value to the society. After laboring in the editorial harness for two years he became blind, retired and was succeeded by Dr. F. J. Felsecker. Saint Vincent was a frenchman by birth, but had served in the Prussian army, was a staunch Catholic and had considerable influence with the authorities of the church both in this country and in Europe.

In 1852 Peter V. Deuster appears upon the scene as a publisher. He had learned the printing trade in The Wisconsin Banner office, and began the publication of the first literary paper in the German language in Milwaukee, Der Hausfreund, which he issued for a short time, and then went to Port Washington. There, to use his own words, “I edited a weekly paper, studied law with, George W. Fisher, was deputy clerk of the court, and in the evening I taught school. In addition to this I had the only abstract of titles in the country, and had a large amount of work to do to keep the books written up to date. When Ozaukee and Washington counties were separated, some one stole volume M of Mortgages which gave me a monopoly of the business. The missing volume was found ten years later in a vault in Blake’s building.”

Mr. Deuster was a busy man, but then it must be remembered that none of the duties he had to perform would approach anything like the demands that would be made upon him by any of the positions at this time.

In the meantime The Seebote was being edited by August Knorr, the stock of the company had passed into the hands of August Greulich, Philip Rickert and Nicholas Paul. In 1856 Mr. Deuster returned from Port Washington and purchased Paul and Rickert’s interests in the paper, and in company with Mr. Greulich published the paper until 1860, when the latter retired. In 1867 they erected the building on Mason street, the last home of the paper.

While The Seebote was a Democratic paper, and its editor, Mr. Deuster, an uncompromising member of that party, it opposed the party nominations for county offices in 1858, and succeeded in defeating them. The conventions were then controlled by a little clique of politicians known as “The Flour Barrel society,” from the fact that it held its meetings in a store on Market square, and the members sat about on flour barrels, discussed the situation and made up the “slate.” In that year Capt. Barry was elected county treasurer and Samuel Waegli register of deeds on the People’s ticket. Both of them were afterwards drowned in the Lady Elgin disaster.

Another German paper was started by Christian Esselen in the meantime, The paper fell into the hands of Bernhardt Demschke, and later W. W. Coleman, who had been bookkeeper in the paper warehouse and type foundry of Josiah Noonan, became associated with Mr. Demschke, and in 1861 they brought out the first number of The Herold, the first Republican German daily,. which has recently secured control of The Seebote.