Monday night I attended a great lecture at Turner Hall by historian Paul Buhle and his wife, Mari Jo Buhle of Madison. Both are well published, retired academics with books chronicling the American left, activist and protest movements. They gave separate talks about the German progressive legacy in local and state politics which developed from the wave of immigrants known as the 48’ers. Mari Jo Buhle talked about early German American feminist Mathilde Anneke who was a fervent abolitionist and worked with Susan B. Anthony for women’s rights in the mid 19th century. She also talked about Socialist leader Victor Berger’s wife, Meta, who was elected to the School Board of Milwaukee with the help of the women’s vote in 1909. This was the first time women had the right to vote in Milwaukee but was limited to voting for members of the School Board.

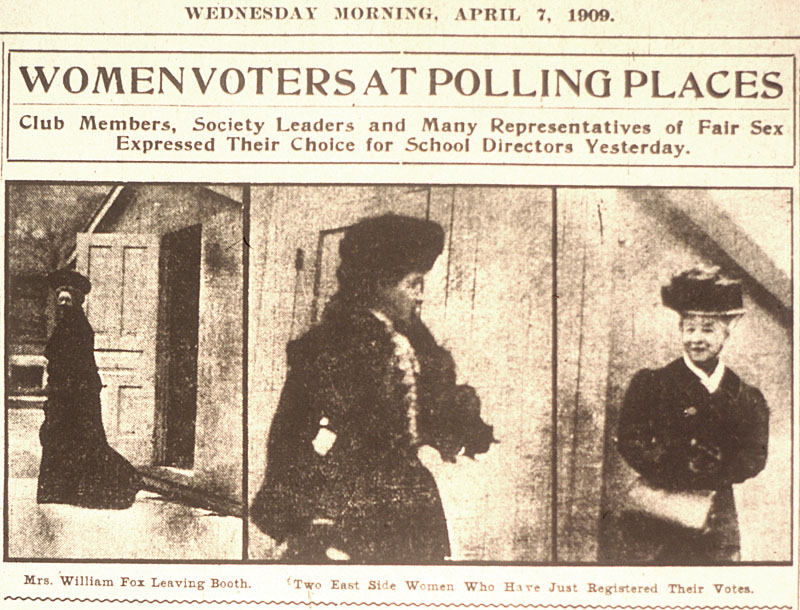

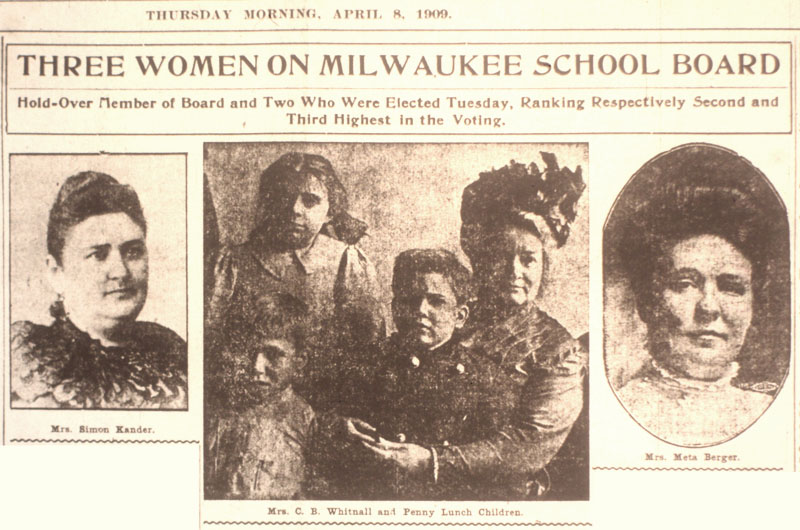

Milwaukee’s society women came out in force during the April 6, 1909 election. It was a badge of honor to exercise this new found right to vote even though the power was limited. But sometimes the first steps are the slowest. Estimates of the number of women that voted ranged from 2,000 to 5,700. But the results were that three women were elected to the School Board; Meta Berger, Mrs. Simon Kander, and Mrs. C.B. Whitnall, all of whom had a profound effect on the Milwaukee school system.

The big local progressive issue of the time was one pushed by Mrs. C.B. Whitnall and the Women’s School Alliance. It was something they had spearheaded several years prior – to provide school lunches to underprivileged children who might otherwise not get enough to eat. The program that was started was called the “Penny Lunch” because it provided a full lunch for the cost of a penny. It stemmed from the idea that children who were well fed will do better work than hungry children and will develop better. Dull children or unruly children became “docile and good students.” The low price gave the families the feeling that this was not complete charity and allowed them some feeling of self-respect. It was very successful since its start in 1902 and was funded by donations for many years to cover the $1,500 a year that it originally cost.

Initially the lunches were provided in the home of Mrs. Jennie Tietz near the Tenth District School and slowly expanded to other schools but by 1907 as the program grew, permission was granted to hold them in the schools. It took until September 1917 before the School Board took over the work and started serving the children lunches with a budget cost of $2,000/yr. Schools did not begin to have specially built cafeterias where children could eat en-masse until after World War I. By 1939, the system was serving hot lunches in all schools and had an annual budget of $23,254 of which only $1,600 was paid by taxpayers. The majority of lunches served in grade schools were fully paid by parents and the remaining lunches of poorer students were free.

Milwaukee Free Press, March 31, 1909 – Advantages of the Penny Lunch

Milwaukee Free Press, April 7, 1909 – Women Voters at Polling Places, Thoughtful Women Turn Out At Polls

Milwaukee Free Press, April 13, 1909 – Penny Lunches For the Children